Border Debate Brings to Bear Fundamentals of Sovereign Nationhood

The choice between security and the 'state of nature' is obvious.

During the Biden administration, and into the Trump administration, Americans have been hotly debating policies regarding immigration, including the benefits and consequences of immigration and what the appropriate immigration policy should be.

Lost in this debate are some obvious distinctions between legal and illegal immigration as well as between mercy and justice for citizens and toward those who harm citizens.

It is odd that this debate is happening, because the principles are fundamental. But we are seeing emotionalism over reason in many of these debates. Some of this may be the unfortunate result of schools fostering emotional fragility and not encouraging critical thinking.

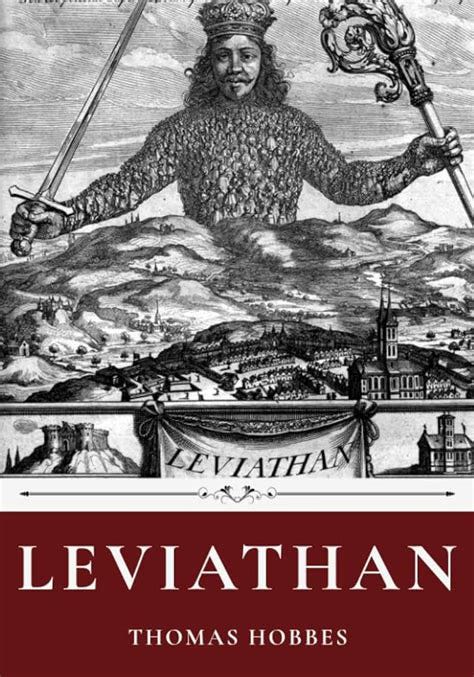

Some good critical thinking is in order here, going way back to why we have nations in the first place. Philosopher Thomas Hobbes addressed this in 1651 when he wrote “Leviathan.’ A famous summative quote from that book is that without the sovereign, or someone form of governance in control, i.e. a government, humans would live desperately in the state of nature, in which he described life as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.”

This concept was captured in a work of fiction called “Lord of the Flies” by William Golding.

To not have to live in a state of darkness where evil prevails, we give up some of our freedom to a sovereign authority-be it monarchy, aristocracy or democracy—so that we are protected from harm within and from outside the borders of a sovereign state.

This exchange is known as the “social contract” or a covenant. But in the past four years, with an open border and an increase in foreign gangs or individual attacks on citizens, the government has broken that contract. Citizens were afforded neither mercy nor justice as criminal aliens were not prosecuted or removed.

A new administration is simply restoring the social contract, honoring our laws, protecting citizens. Many feel we have barely escaped a return to the state of nature. Others bizarrely object to a return to order in the social contract.

Since the confusion continues, a return to Leviathan, particularly Book 2 “Of Commonwealth”, chapters 17-19, clarifies why we have nations, and why nations have and protect their borders.

First, Hobbes addresses how nations form. It has to do with the fact that humans are rational. Individuals come to realize that the state of nature is indeed unpleasant, and by logical thought they conclude that life would be better if they form agreements with others for the sake of mutual security. These agreements constitute the covenant that makes a nation—often these are expressed literally in constitutions.

Once formed as a nation, Hobbes asserts that all those who have made the covenant that created the sovereign, the subjects, are obligated to obedience. They do this out of fear of punishment, but also because, as Hobbes says, each man is the “author” of the sovereign and therefore naturally obligated to obey.

Also, all those who enter the sovereign state are also obliged to obey the laws, because implicitly they enjoy protection from the state of nature and it is therefore implicit that they obey the laws of the sovereign state. If a foreigner violates laws and especially if they bring the state of nature into a sovereign state, then they are not entitled to the protection afforded in the covenant they violated.

The sovereign can do no injustice when it enforces its laws because the sovereign was created by a covenant among the people to do, as indicated in Hobbes’ definition of a commonwealth, “as he shall think expedient, for their peace and common defence (sic)”.

It should be obvious that cities receive both mercy and justice from the government based on their observance of the law. It should not be a stretch that immigrants receive either mercy or justice based on whether they obey the law also, both in the manner they come into the nation and how they behave once here.

The Leviathan lurks in the political debates today about policy, which unavoidably stem from the original purpose and role of government.